Outrage! Scandal! These must have been the battle cries of petition given by Count Aymo Maggi, Count Franco Mazzotti, and their friends Giovanni Canestrini and Renzo Castagneto when discussing the Italian Grand Prix relocation to Monza in the city of Milan in 1922. Much like the citizens of many other industrializing nations, Italians were deeply embroiled in a passionate love affair with the automobile during the 1920s. In particular, there was a fervent appreciation for motorsports among Mediterranian peninsula’s denizens. So when the most illustrious race in Italy was taken away from the Counts of Brescia, they retaliated by founding their own event four years later.

Together, the four founders ironed-out the details of the race, which aimed not only to return motorsport publicity to Brescia but also engender the spirit of competition to Italian auto manufacturers. In lieu of creating a closed-circuit track, now considered trite due to Milan’s Monza, the quadrumvirate agreed upon a single-lap public road rally that would bring racing excitement directly to the hoi polloi of villages along the route from Brescia to Rome and back around. Round trip, the race’s figure-eight journey across the countryside would barely eclipse 1600 kilometers or 1005 miles, appropriately meriting the appellation “Mille Miglia” or thousand miles in Italian.

With their collective power and the support of several wealthy confederates, in 1927, the first Mille Miglia race began on the 26th of March. Although the field of drivers was almost entirely comprised of Italians, aside from knowing the sheer grandeur of the race’s distance, those inceptive seventy-seven participants, comically had almost no perception as to how many hours the event would endure for. As such, many teams showed up to race day in their unmodified production cars packed-full with overnight bags. Although sanctioned by the Italian government, the race route was still charted throughout openly public roads. So, to enforce some safety, several thousand soldiers were commissioned to maintain crowds when possible and drivers were encouraged to abide by traffic statutes – very few, if any at all, did. Then lastly, to prevent foul-play, fourteen check-points were established throughout the course to monitor positioning and ensure that drivers did not take advantage of short cuts.

Similarly, to the driver’s nationalities, the field of vehicles was also almost all Italian. Fiats, Lancias, Alfa Romeos, the now-defunct Officine Meccaniche (O.M.), and Count Maggi’s personal Isotta Fraschini driven by himself all comprised the majority of the roster. Beginning with the largest displacement participants, the Count’s massive 8-liter Isotta was the first to roar away from Brescia at 8 o’clock that morning. It had begun. Although a skilled wheel-man, within the first leg of the trip, the mighty Isotta was forced to concede its position to a smaller, quicker Alfa Romeo RLSS. As the race progressed on, attrition from driver abuse, mechanical failures, and the road quality began to take its toll on teams. Shortly after racers rounded Rome, an oil pipe issue removed the leading Alfa, and with the onset of twilight, observers illuminated the route with fire torches for the remaining drivers.

Shortly following the twenty-one-hour mark, O.M. supporters became overjoyed as three Tipo 665 cars passed in rapid succession across the finish line. Lancia was next to follow, and the Count’s Isotta screamed across the stripe to secure his sixth-place position. By the conclusion of the race, attrition had reduced participation by 23 cars. Moreover, the winning O.M. triumphantly secured the top podium position by averaging a contemporarily impressive 47.9 mph! Celebrations ensued in Brescia and with its success, il Duce Mussolini took note and decreed to the race founders that the event would continue annually.

By the time of the race the following year, the entry list had swelled to 83 vehicles with several foreign makes amidst those ranks. This year the route remained identical and as such, returning drivers confidently increased their speeds. Coincidentally, these higher velocities resulted in an intense competition that was nearly two hours shorter than in 1927. This year though, it was Alfa Romeo’s new 6C that took the checkered flag, establishing the first of three consecutive wins at the Mille Miglia for the Milanese car creator.

By the third year, the Mille Miglia had dramatically begun to pick up traction, especially inside Italy. Although non-Italian automobile entries were still scarce, overall participation was up. Most notably, this was the first year that the Bologna-based racing company, Maserati, fielded a car. Just one year later and registration had essentially doubled, now including the preeminent Scuderia Ferrari. It was also around this point that race organizers established their eccentric car launching tradition. Unconventionally, the slowest vehicles with the tiniest displacement were the first to initiate the race, followed then by the challengers in ever-increasing higher performance cars. It was a decision which aided the event by holding the pack more closely together, thereby reducing road usage.

Throughout the thirty years and twenty-four races of the Mille Miglia, only three times has a non-Italian competitor secured an overall victory – 1931 was the first. Germany’s Mercedes-Benz inaugurated themselves to the Brescia run in 1930, finding just enough footing to impressively grab the sixth place prize merely one hour after the race leading Alfa concluded his run. However, with the world economic crisis, Mercedes was looking to withdraw support in the upcoming year. With a touch of negotiating and an agreement for the exchange of some prize monies, Mercedes lent driver Rudolf Caracciola, his wife, co-driver, and their only mechanic a specially lightened factory SSKL and their support. Fortune, talent and Germany’s durable engineering paid off that year, though, when Caracciola’s supercharged SSKL blasted across the finish line eleven minutes before his next competitor after averaging a record-breaking 96 mph!

Yet, as the world persevered through the turmoil and poverty of the economic crash, the Mille Miglia suffered as well. Although the race would continue until 1939, contenders dwindled during this period since few could afford such frivolity. However, notwithstanding the diminutive ranks, the horsepower and top speeds of those that did enter soared higher, and higher.

Moreover, no team was as surefooted or capable of reaching these rates than Alfa Romeo. For seven consecutive years, Alfa and their indomitable 8C race car would triumph in the Italian classic, bringing an exhilarating high-speed spectacle to onlookers year after year. Nevertheless, 1938 proved as a grim reminder to racers and onlookers just how dangerous this public-road rally was when an amateur team, who lost control of their Lancia, careened into a crowd, sadly killing ten (seven children) and injuring many more. Immediately, Mussolini prohibited the following year’s event.

With the drums of war thundering just over the horizon, the final Mille Miglia before World War II was held in 1940. The racecourse was truncated into a 104-mile triangular circuit which required nine laps to complete. In many ways this was a race of firsts: BMW participated with five highly-optimized 328 wearing soon-to-be revolutionary aerodynamic designs, and Enzo Ferrari fielded his two AAC Tipo 815 which were the first cars he hand-built and designed. Unfortunately for Enzo, both entrants would end their races early. Alfa Romeo, despite strong contention, simply could not adequately compete against BMW’s aerodynamically superior Superleggera design, resigning themselves to second and fourth place among the other 328 racers.

It would take two years after the conclusion of the second world war for the Mille Miglia to return. By that point, Italians were eager, if only even briefly, to forget their current state-of-affairs and celebrate a prideful national pastime. The racecourse returned to a layout as similar as possible to the original route, a challenge provided by the still significant roadway destruction inflicted by the war. Ferrari also entered his first-ever eponymous automobile into the competition, the evolutionary 166 S. Notwithstanding the rampant fuel and rubber shortages, special arrangements were secured to provide participants with these essentials and that year Alfa Romeo again reigned supreme, but that was all about to change.

If during the prewar years, Alfa Romeo is considered the force to be reckoned with, then in the postwar Miglia, the team to fear was Ferrari. From 1948 until 1953, the Maranello monster stood atop every podium. This era also ushered in greater, more unfathomable road speeds and considerably significant increases in registrations. In 1948 alone there were over 300 entrants, ultimately resulting in the invention of the Mille Miglia’s unique numbering system. In order to monitor this multi-class mayhem, each car was now brandished with a three-digit sequence which represented their car’s race identity and the time that they crossed the starting line.

As Europe collectively resurrected itself from postwar depression, 1952 brought Porsche and Mercedes back into the race and Jaguar, Aston Martin, Healy, Renault, and Panhard further broadened the roster of international competition. Provided with such a vast array of entrants from all over Europe, during 1953, the World Sports Car Championship smartly folded the race into their lineup. Although the route had slightly changed since the first attempt in 1927, the mileage traveled remained consistent. However, innovative aerodynamics espoused with the top competitor’s horsepower ratings now lingering around the 300 mark, the advancement of the automobile throughout the decades was indeed evident when Ferrari’s 340 MM Spider finished the race that year eleven hours faster than in 1927.

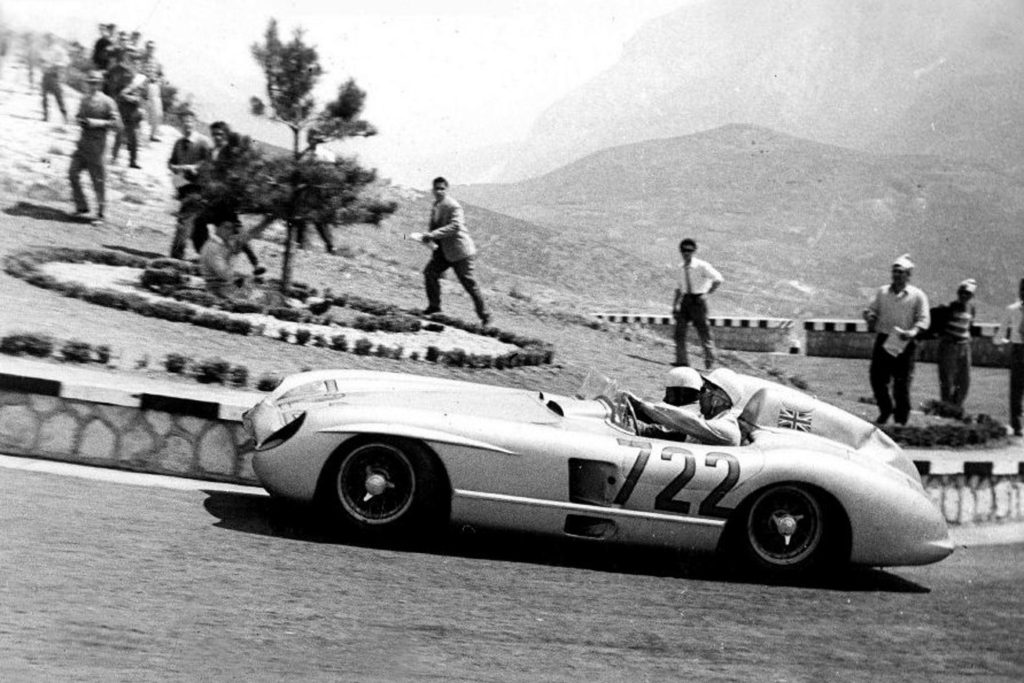

As mentioned earlier, only three times has an international team won the Miglia. 1955 was the final year and may resolutely be the most legendary running of the race ever. Two months prior to the starting day, Mercedes-Benz was already out for blood. Four purposefully designed 300 SLRs, heavily based on their current Formula 1 car, were entered, a massive team of sixty race mechanics was reserved for the event, 20,000 pounds were set aside for funding, and four world-class drivers were enlisted (Juan Manuel Fangio, Karl Kling, Hans Herrmann, and Sterling Moss). During those sixty days before the event, each of these drivers was dispatched to Italy to drive and memorize the course intensively.

By race day, the Mercedes teams were ready. Slightly before 0700, the 300 SLR of Fangio began rolling past the starting line. At 0722, Sterling Moss and co-pilot Denis Jenkinson were dispatched from the grid amidst the sonorous and seraphic scream of the 310-horsepower 3.0-liter straight-eight engine. Accompanied by a 15-foot roll of course notes, Jenkinson held on tightly as Moss expertly piloted the sleek Mercedes to speeds in excess of 170 mph along these still very much public roads! It took only 10 hours and 7 minutes for the team to arrive back in Brescia that day, earning Mercedes their second Mille Miglia trophy. That day, Moss set a record time with a record average speed of nearly 98 mph, an achievement that would never be broken.

After that year, it would be Ferrari who would win the final two years of the Mille Miglia race. In 1956, the most significant number of participants – 365 cars – would take off from Brescia. However, by now only Ferrari and Maserati were fielding full factory-backed efforts. At this point, severe crashes due to speed had becoming scarily frequent, not only because of higher velocities but also due to the sheer number of racers involved. Although Ferrari would win during that last year with a 315 S, 1957, another one of their entries, a 335 S, would suffer a tremendous tire blow out causing a failure of control and the loss of nine lives. Elsewhere on the course, a Triumph TR3 would crash, taking the life of the driver. The race was indefinitely postponed for 1958.

In the cumulative twenty-four races held, 56 people’s lives were cut short by the Mille Miglia. Indeed, the public road use was a contributing factor, but so too were weather conditions, wandering animals, high speeds, incompetent drivers, mechanical failures, and spectators constantly willing to risk their lives for a closer look. Nevertheless, the Mille Miglia is deserving of all of its laurels and renown. Not only did it bring together famous marques like Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati, Lancia, Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Porsche, Aston Martin, Bugatti, and many more, but did so in such a grandiose participation level that the word epic is genuinely applicable. The competition is analogous for establishing many postwar rivalries while furthering the fascination and development of the sports car – and it all took place across a thousand miles of back-country streets!

Christopher Fussner is the Editor-in-Chief here at WOB Cars and MotoringHistory.com. He writes at his home in Los Angeles, manages a car collection, has a genuine passion for cars and racing, a love of Star Wars, and his favorite dinosaur is Carnotaurus. Did we just become best friends?