When reflecting on a remarkable life or an epic of events, it is natural to see how the word “fate” can aptly be attributed. The right time, the right place, and the right people becoming perfectly intertwined, resulting in historical immortality. The proper mixture of those can ignite a spark that sets passion ablaze for the tale of how it all came together. Although Porsche’s 917 was designed to be “the best, everywhere,” it is clear that what intervened was, in fact, fate. It is an outcome of the most impressive level because the legacy that it left dramatically overshadows all other racing cars.

In 1968, Porsche’s racing division was being run by Ferry Porsche’s nephew, Ferdinand Piech. Piech was, above all else, a racing fanatic and was so driven to win that his select team operated at a near limitless expense. Part of why he had such a large budget was that Porsche had long used racing, instead of traditional marketing, for promotion. Racing also served a dual purpose for the brand by improving the quality of their standard production vehicles. Yet despite Porsche’s participation in the World Sportscar Championship (WSC) since 1951, it never competed at the highest performance categories within the series.

However, to attract new competitors to the WSC, the FIA announced new rules in 1968. This rule change worked to curb the massive 7.0-liter V8 Ford GT40’s that had dominated the series by limiting displacement to 5.0-liters. Now seeing opportunity, Porsche arrived that year with the 3.0-liter 908, determined to win, especially at Le Mans.

It came as a shock to all that year though when Ford pulled off their 3rd straight victory with a revised 4.9-liter GT40. Although disappointing for Porsche, that Ford GT was closely followed by a 907 and one of the new 908 models – an impressive feat for their first attempt. Now that Piech knew his team was close he devised a strategy to help them secure the win next year. After noticing what Ford had done with their GT program, building a large displacement car that just barely skirted below the maximums, the Porsche team decided to mimic their approach. Called the Porsche 917 this new race car was heavily built upon the 908 but taken to even further extremes and greater expense.

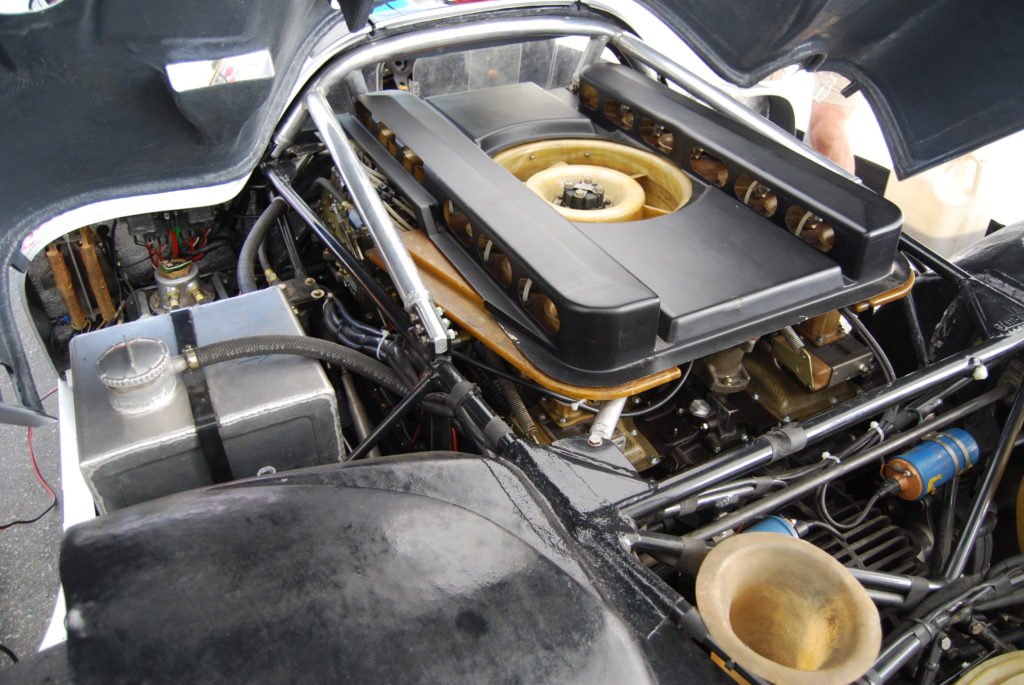

To achieve this higher displacement, Piech chose to enhance the 908’s flat-eight motor with four more cylinders, thereby creating Porsche’s first flat-12. That engine was then bored and stroked out to 4.5-liters, just below the legal limit. To lighten the motor, engineers liberally employed exotic metal alloys, titanium, and magnesium that were all learned from the ‘Bergspyder’ – a hill climb variant of the 908. The ingenuity practiced by Piech’s team to save weight around the car is simply remarkable. The lightweight, tubular aluminum frame, which scarcely weighed more than 100 lbs (45 kg), was hollow and functioned as piping to the front oil cooler. The gear lever was made of wood, the body paneling paper-thin fiberglass, the new wishbone suspension was aluminum, and suspension springs were made of titanium, even the key was drilled with holes to minimize weight – nothing was too cost-prohibitive, it would seem.

When finished, the 917 was unlike anything else built before it and soon the labor-intensive construction posed a new issue for the team. See the FIA’s rules to incorporate new manufacturers also stated that manufacturers needed to have 25 cars constructed to meet homologation regulations. Porsche had merely six 917 intact. When the FIA came to examine the car they said it passed inspection but could not compete unless the outstanding cars were built. With their 1969 season now in jeopardy, Piech rushed the remaining cars into production.

With production well underway, Porsche set about road and track testing its new champion. However, it soon became evident that rushing production on a race car does not bode well for performance. Despite all of the technological advances and money put into the 917, testing revealed it to be almost impossible to drive safely at the limit. Word quickly spread among professional drivers and in the first race of the 1969 season the 917 would not run and in the second would finish 8th from a lack of driver support. During the third race that year, Le Mans, their fear would become validated when a Gentleman driver fatally crashed. Ford would go on to win the race, followed by a 908 less than 30 meters behind it. Piech’s torchbearer was ostensibly coalescing into nothing more than a failed 908 variant. But then, fate intervened when the renown John Wyer’s Gulf racing team took an interest in the car.

Wyer, who was running the winning Ford GT40’s in 1968 & 1969 saw promise in the Porsche. So much potential that he discontinued the use of his still successful, but antiquated, GT40 immediately after the Le Mans. Wyer’s team knew that if they were to win with this car, they would first need to correct the wheelspin and stability problems encountered at the 200 mph plus top speeds the 917 was capable of. What they engineered was the first real use of downforce in endurance racing and would change motorsports forever. They discovered that by attaching two aluminum tailpieces to the 917’s decklid the air flowed further beyond the rear body, resolving much of the car’s handling instability.

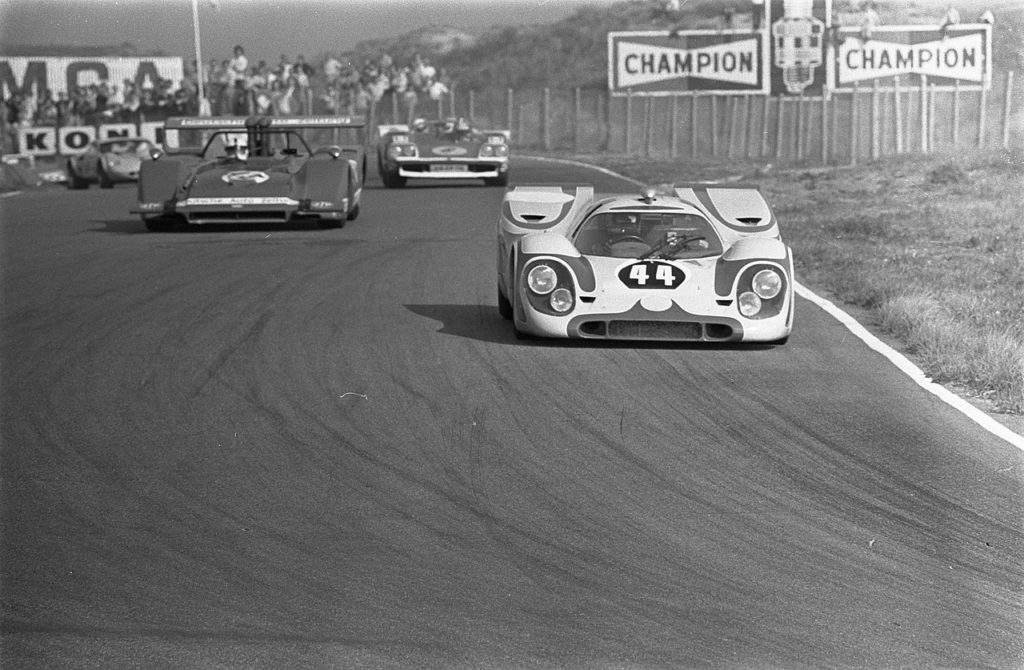

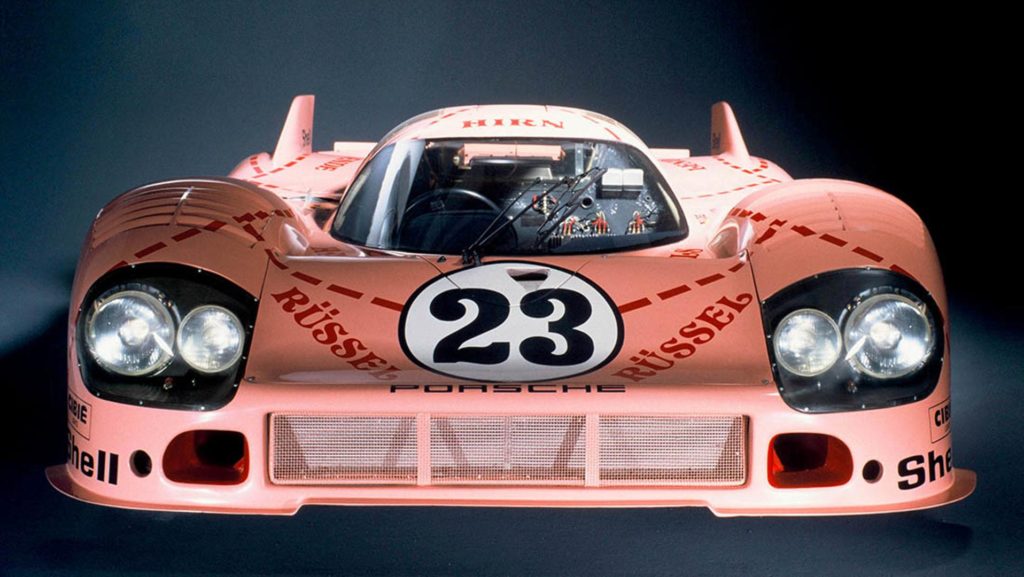

At Le Mans, 1970, three Porsche teams (Gulf Wyer, Martini, and Salzburg (the Porsche factory team)) showed up sporting their newly improved 917s. Two distinct variations would race this year, a 917 LH “langhecks” (long-tail) and 917K “kurzheck” (short-tail). The 917LH was a low-drag car like the 1969 version, but thanks to the downforce discovery were more planted at an even higher top speed. The 917K, in contrast, had a stout, short-tail section designed to sacrifice high speeds for turning capability. Although the 917LH was favored to win at Le Sarthe, it was the #23 red & white 917K of Porsche-Salzburg, which had started in 15th place, that brought Porsche their first Le Mans triumph. The victories didn’t stop there as Porsches swept the podium, taking second, third, and two other lower class wins!

Wyer’s addition of the aerodynamic aids was so impactful that the 917’s dominated the entire series that year. Taking victory after victory at Daytona, Monza, Spa, the Nurburgring, Watkins Glen and many more. The 917 won so many races that in 1971 everyone wanted to be driving a Porsche.

1971, for Porsche, turned out to be not just a year of records but, at Le Mans, a race of records. Engine improvements upped power to 630 hp and, despite its propensity to deflagrate, the frames were made of magnesium, to further reduce weight. With these enhancements Porsche would win Le Mans again, taking first and second place.

The legacy of the 917 starts in the numbers it set in France that year. Jackie Oliver would smash the fastest lap record, setting a time of 3:18.4 with an average speed of 151 mph (244.3 km/h), it would take 37 years for someone to surpass that. In qualifying a 917LH set a time of 3 minutes 13.9 seconds, averaging 155 mph (250 km/h), it would be 14 years before someone beat that record. The 917K also set a distance record that would not be broken until 2009, 39 years later, driving an astonishing 3315 miles (5335.3 km)! That season the 917 won eight out of ten World Sportscar Championship races, effortlessly capturing the trophy.

Unfortunately for Porsche, the FIA were not nearly as smitten with their success. The FIA levied rules that effectively banned the 917, and cars like it, from the 1972 season. However, Piech was not done yet and set his sights on other conquests – specifically the Can-Am series.

Over in the United States and Canada, a nine-race series has begun in 1966 known as Can-Am. Here, in a category called Group 7, Piech found his car’s new calling. Outside of requiring two seats, a closed wheel configuration, and some slight safety measures, there were no other category restrictions – it was sheer lunacy. Although, 917/10’s (the spyder version of the 917) had been participating since 1969 but had found little success. With no factory support from Stuttgart, the 917/10 was simply being outrun. Their 4.5-liter engines were inadequately suited to compete against the 9-liter Chevrolet motors in McLaren’s cars. But, that all changed when Piech’s team stepped onto the playground in 1972.

Originally Piech wanted to build a flat-16 motor for Can-Am by adding four more cylinders to the 917’s flat-12. But then another stroke of engineering fate hit the 917 – turbocharging. Piech’s team found that they could significantly increase power over that of the flat-16 and all with less weight by adding two turbochargers to the car. The results were mind-bending: 850 to 1000 horsepower while in racing trim. Cars were modified with large spoilers and steeply raked front bumpers because the massive power made drag limitations irrelevant. With the factory-supported effort, the 917/10 run by the Penske team would win six of the nine races during 1972.

Then, in 1973, the final year of the 917’s career, all of the past success culminated into what makes this car so mythical, the 917/30 was born. Porsche revamped the motor to a displacement of 5.4-liters, which allowed it to churn out over 1100 horsepower. During qualifying Porsche would turn up boost even higher, to 39 psi, resulting in 1500 horsepower! Even by today’s measurements, it stands as the most powerful sports car racer ever produced for a series.

The 917/30’s unrelenting power and featherweight figure, 800kg, helped it lay down performance numbers of biblical proportions. 0 to 60 mph (100 km/h) in 2 seconds, 0 to 124 mph (200 km/h) in 5.3 seconds and onto 186 mph (300 km/h) in just 5.9 seconds more. The car would ultimately top out at around 240 mph (390 km/h)! Needless to say, Porsche won the 1973 series, losing only a single race.

After sweeping another series, the 917 was faced with a familiar story – it was again banned from racing. The Can-Am series, attempting to limit Porsche’s success, introduced new fuel regulations that would effectively hinder its 917s competitiveness. Although some 917/10s continued to race by private teams, the factory-backed effort withdrew from the series for 1974. Thus ending its reign of success (or terror).

The most famous events in our world’s history have been well documented in film and literature. They are enduring testaments to the heroics and innovations that should inspire awe. There are numerous books written about the 917’s success and development. Further proof of how prodigious the 917 was is the fact that Steve McQueen’s movie Le Mans – widely considered the most famous car movie – is a tribute specifically to Porsche and that phenomenal car. The 917 was a racer that was so good, so inspirational, that an entire film was predicated on it winning a race for Porsche.

Beyond its career the 917 lived on as a benchmark, pushing engineers to develop better aerodynamics, turbocharging, engines, and materials that could beat the outrageous records it set. In five years the 917 took Porsche from relative obscurity and put them onto a path that has made it the most successful motorsport marquee in the world – that is fate, that is immortality.