At the end of 1988, a Porsche 911 (G-series) left Stuttgart destined for sale somewhere in the world, thus contributing to a total of 32,000 Porsches sold that year. In 1989, Porsche began selling its successor, internally known as the 964. Touted as the “911 for the next 25 years,” it indeed seemed up to the challenge. Some 80% of the 964 was made using newly designed components, with a few directly derived from the prodigious 959 supercar. However, four years later, Porsche was in financial moribund, with total sales lingering around 12,500 units worldwide and falling.

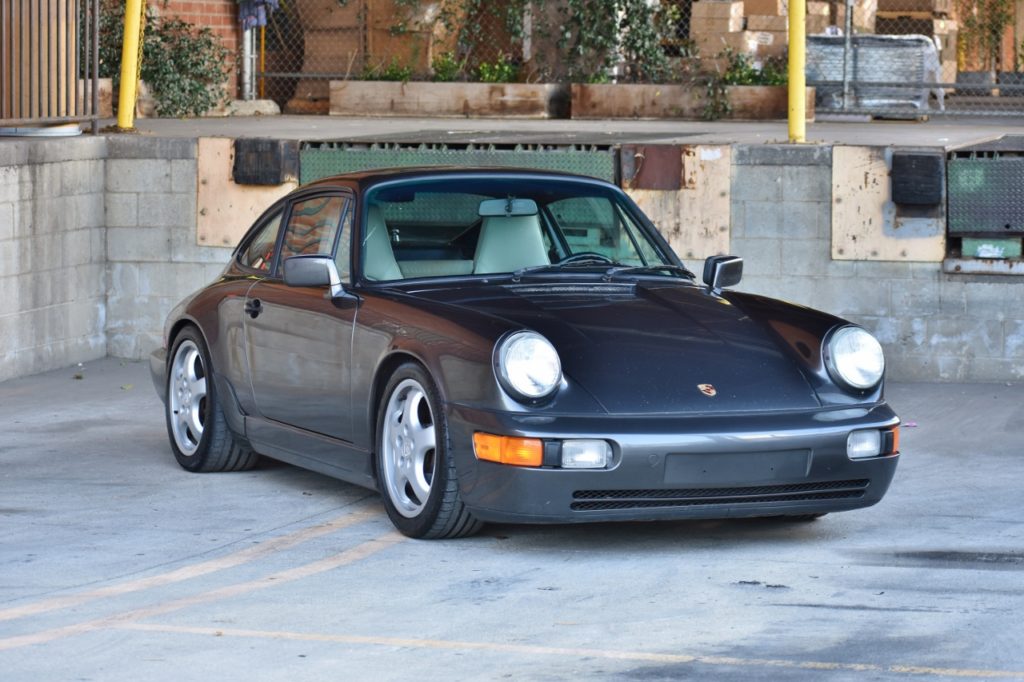

Although improvements were happening the initial problem was that with the 964, it was the first time Porsche had wholly redesigned the car. The redesign proved a costly and risky move that came with some irreversible issues. To start, the new aesthetic immediately drew criticism from the press and potential buyers. The 964 retained a classic 911 silhouette, but the new bumper restyling (although aerodynamically superior) appeared turgid and ill-fitting. The next aspect that born judgment were the mechanical innovations, specifically the modern all-wheel drive (AWD) Carrera 4 (C4) model that was widely exhibited and produced.

With the AWD arrangement, Porsche’s goal was to make a safer (less apt to oversteer) 911, and they did. However, AWD was still revolutionary in that era, and the cumbersome system was vampiric, sapping feeling, power, and precision from the 911. Brand loyalists immediately disliked the compromised steering feel and languid nature. Agility and accuracy were integral elements in the first 911 formula, and the 964’s tepid constitution underwhelmed drivers. Altogether, the sacrificed performance and lame aesthetic made for a 911 that only returned low sales.

By the end of the 964, it had only brought Porsche a meager 8,341 units sold. It was a precise figure with a foreboding conclusion; significant revisions to the 911 had to be made to help turn Porsche around. Thankfully, a descendant was already in the works at Weissach.

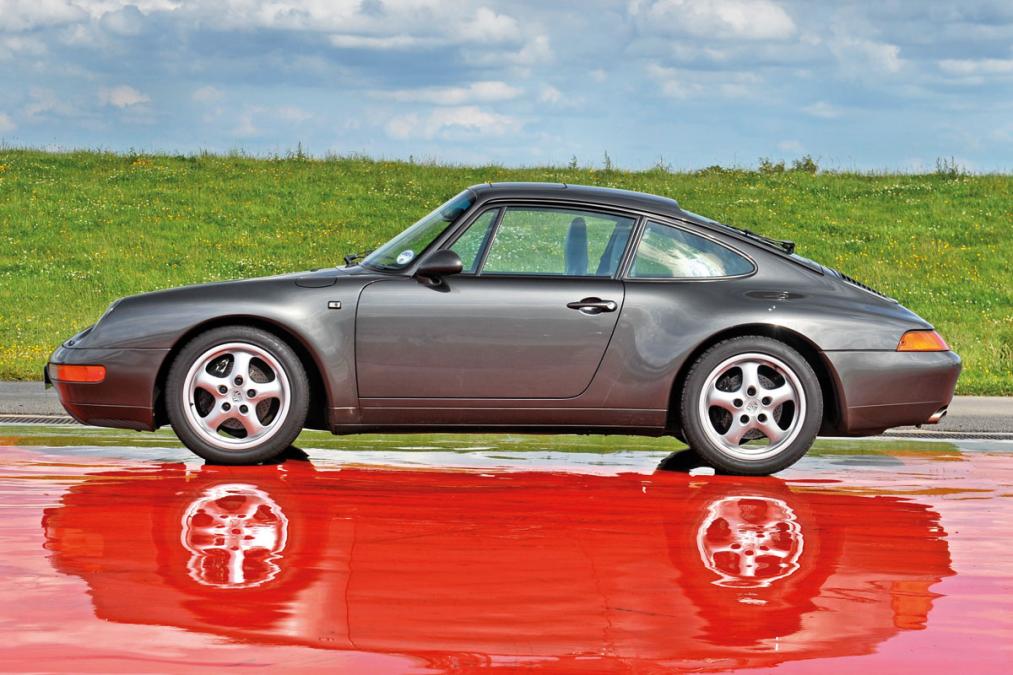

In the warm summer air of 1991, the earliest testing of the 993 prototype finally began. Even at that time, the 964’s shortcomings were well known, and Porsche was diligently crafting the 993 into what it should have been. Lead designer, Tony Hatter reflected on the first steps of correcting the shape: “With the 964 the 911 had kind of gotten out of balance, with its big fat bumpers in the front way up in the air and the rear end hanging down. We addressed the complete proportional balance of the car. That was the main goal.” Hatter energetically tailored a “finely trained athletic shape” with precisely proportioned bulges and trimmings. All of this surfacing refinement led to a broader body, yet the drag coefficient was only marginally (0.01) higher thanks to smoother transitions between panels. With the physique set, next came the balancing of the performance.

To do this, Hatter consulted Peter Falk, an esteemed engineer of Porsche’s competition teams. At great length, he discussed with Falk the tenets of how a 911 should feel. Falk further embraced this task by preparing an in-depth analysis of the ethos of the 911. In his report, he examined comparisons between Acura’s NSX and the (964) Carrera 2. The Carrera 4 was excluded from the paper since it had entirely tamed the 911’s spirit. The research concluded that the agility (the responsiveness of a vehicle) is what had been exorcised. This final piece of information gave Hatter and his team a solidified concept of the production-ready 993.

Throughout the remaining months before its release, Hatter and his team scrutinized every 993 component. However, the most radical change came in the form of a new multi-link rear suspension setup. This organization hosted coil springs, a “Weissach” rear axle to actively counter acceleration squat and lift-off braking oversteer, and mounted all the elements to the subframe. This mounting point further reduced road noise while providing greater vehicle rigidity. The 993 was also buffered with state-of-the-art automatic braking system programming. The system rewarded drivers by beautifully blending sublime stability with the 911’s inherent edge.

To eliminate the straights, engine power was uprated to 272 horsepower at 6,100 rpm with 243 ft-lb of torque coming to the wheels at 5,000 rpm. Pushed through a new six-speed (G50) gearbox the new motor provided a 26-horsepower improvement over the 964 unit. The extra ponies were tapped by reworking the exhaust system, reducing valvetrain mass, and through advancements with self-adjusting hydraulically operated valves. A side effect of which was that servicing 911’s became simpler since the design eliminated the need for valve adjustments. Together their teamwork blessed the Carrera with a lofty top speed of 168 miles (269 kilometers) per hour!

While the 964 Carrera 4 had excessively tamed the 911, Porsche didn’t want to dismiss an AWD option from the lineup. Instead, engineers adapted by injecting much-needed vitality to the equation. By mid-1995, the Carrera 4 was launched. Gone were the hefty computer-controlled differentials, clutches, and bulky planetary gears of the previous system’s front differential. In its stead, a distinct viscous coupling and torque tube combination afforded 50% less mechanical power loss. Plus, this tinier packaging reduced the differential’s front-trunk incursion, thereby increasing storage, and also displaced 110 lbs (50kg) of weight compared to the prior unit.

Utilizing that same all-wheel-drive system, after a brief hiatus from the model lineup, the Turbo was back! Sporting 408 horsepower the new Turbo pulled off runs to 62 miles per hour (100 kilometers) in a staggering 4.4 seconds. From there it continued its charge onward to an aerie 180 mph (290 kph) top speed! They say teamwork makes the dream work and making this extreme speed dream a reality was possible because of an additional turbocharger. By adding a second turbo, and reducing the size of both units, Porsche was able to eliminate the turbo lag that plagued previous Turbos and add more power.

Not lost on the 993 Turbo was the aesthetic appeal of the previous wide-hipped Turbo models. The latest Turbo came with extended fender bodywork and large front ducts for cooling. Despite the added body paneling, extra engine equipment, and the standard Carrera technology, the Turbo gained 20% torsional rigidity with only an additional 66 lbs (30kg) of weight!

For buyers assuming that all-wheel-drive domesticated the Turbo, there was a remedy – the GT2. Launching at the same time, the widowmaker GT2 took all of the Turbo’s performance goodies, added 30 horsepower (thanks to increased boost pressure), and stripped away the AWD system. Other alterations included a fully-adjustable rear wing that created massive downforce, wider rear wheels with tires that raised traction limits, and liberal use of lightweight aluminum on the trunk lid and doors. Further weight was removed from the interior by taking out anything else deemed non-essential.

Simply put, the GT2 was maniacally fast for a road car, but it needed to be in order to meet racing homologation rules. By December of 1995, 21 would be transformed into road-legal counterparts to their racing brethren. GT Purely Porsche, conducted a road test that year and perhaps summed up the lunacy best. “Full throttle runs along the back straights and committed, deep breath, turn-in attacks on the circuit’s faster curves allows the GT2 to show its promise. The higher the pace the more planted it feels. The quicker you can turn in, the earlier you can get back on the gas and catapult yourself through the horizon… the GT2 may not be the most fluid 911 to steer, or the most confidence inspiring, but in the right conditions, on the right road, on a special day, it will deliver supercar-humbling performance.”

Following the same lightweight homologation recipe on the standard Carrera model, and only available in European theaters was the Carrera RS. The RS stripped away the radio, the power systems, soundproofing, and thinned out the glass to pull over 220 lbs (100 kg ) from the standard Carrera on which it was based. A more prominent, 3.8-liter motor, produced 300 horsepower and introduced Porsche’s newest 911 engine technology – VarioRam.

VarioRam worked by varying the length of the intake runners, taking into account throttle application and RPM conditions. By creating more or less distance for the air to travel, via ducting routes at specific conditions, Porsche could significantly improve power output. In 1996, all-new Porsche 911’s came standard with the VarioRam system, which provided a further 13 horsepower and 18% more torque in the middle RPM range.

That year was also the first year of the Targa, having come out of a roof cosmetic surgery that was polarizing to some. Unlike all previous Targas, which had a removable roof, the 993 sported a sophisticated panoramic sliding glass roof. Some missed the aesthetic of the hoop, a staple of the Targa since its introduction in 1967. Nevertheless, the benefits of this glass panel were undeniable. The glass fixture did not leak, deform, or require lifting and stowing. Additionally, the glass roof allowed designers to retain the traditional 911 side-profile while only adding 66 lbs (30kg).

The second release of the year was the Carrera 4S. In essence, it was a Carrera 4’s engine, and AWD combination mated to a Turbo’s body, brakes, and a limited-slip differential. The concept sounded like a brilliant offering but soon drew criticism from fastidious automotive journalists. The reality was that the penalty for adding all of these extra components, with no additional power, significantly burdened the C4S’s agility. Altogether, it was some 110 lbs (50kg) heavier and 30mm broader than the Carrera 4. These changes made the C4S less aerodynamic and more challenging to maneuver. Yet, braking performance and grip did slightly improve because of the uprated brakes and wider tires.

Thanks to all of these new models and innovations, it was only two years after Wiedeking’s promise to the board that Porsche’s accountants were stowing their red pencils. Wiedeking not only saved the company from financial ruin but by 1996 regained profits, mostly thanks to the reformed 911. However, more radical changes were awaiting the 911 within by the end of the millennium. With ambitious events on the horizon, the 993’s final two years of production (1997 & 1998) garnered few innovations.

In 1997, the Carrera S was brought forth for sale. In the simplest terms, the Carrera S was a standard Carrera wearing the Turbo’s bodyshell. Aside from that, it rested on a lower suspension setting and was blessed with a mild aesthetic enrichment. The Carrera S was identified by model-specific tachometer script, a split-panel rear deck spoiler, and a special color gear & handbrake lever.

At the same time, another small batch of GT2 was built, and these new versions adopted twin ignition, and the boost pressure controls were enhanced. The resulting improvement was 20 extra horsepower for a total of 450. For those who wanted an all-wheel-drive safety net, the Turbo S offered the same 450 ponies but was bespoke with yellow brakes, quad-exhaust tips, side-body air scoops, carbon-fiber interior trim, and new rear wing design.

Ultimately, 1998 was a somber year at Porsche. It signaled the end to a 35-year marriage between Porsche and their air-cooled flat-six motor. A marriage foundation that their motorsports teams, road cars, and heritage over those decades were deeply embedded. However, the reality was that although Porsche was saved from financial ruin and the 911 from its lethargy, the air-cooled motor had become uncompetitive.

Porsche had long-known that the engine was nearing critical conjunction. One where engine cooling, emissions and fuel regulations, and advances in performance were not all possible to be met. Even with the current advancements, especially given the price-point, the 993 was teetering on the fringe of competitive relevance. So, with a heavy sigh, the curtains were closed on the air-cooled 911 in 1998, because thankfully the show could go on thanks to a more water-soluble solution.

Christopher Fussner is the Editor-in-Chief here at WOB Cars and MotoringHistory.com. He writes at his home in Los Angeles, manages a car collection, has a genuine passion for cars and racing, a love of Star Wars, and his favorite dinosaur is Carnotaurus. Did we just become best friends?