It could be persuasively argued that the first autos were all convertibles. Even though the textile/leather roofs of the 1910s were predecessors to our contemporary drop-tops, the reality is that the multitude simply lacked the ability to support a metal cover at all. However, by the 1920s our current employment of the term ‘convertible’ (a roof capable of fully enclosing or exposing a car’s cabin) could aptly be attributed thanks advances in metallurgy, styling, and speed. Although they were now being produced in smaller numbers due to the rising demands in fixed-roof models and the Great Depression, convertibles throughout the twenties and thirties were still available. Despite the construction slow down, numerous car buyers never lost their enchantment for riding around inside an airy cabin.

As preferences toward automobiles evolved, so to did mechanics, styles, and innovations used to lure audiences into showrooms. During the 1950s, automakers keen on inventing new and exciting exterior designs began experimenting with demountable roof panels. Their intention was furnishing drivers with the freedom to turn sporty coupes into sunny, semi-convertibles inside a minute. However, far before Porsche copyrighted their renown ‘Targa’ moniker and long before Burt Reynold’s made the cowboy hat an integral part of any Trans Am’s open T-top experience, there were the progenitors. Chiefly among them, was the legendary automotive designer and Automobile Hall of Fame inductee, Gordon Buehrig.

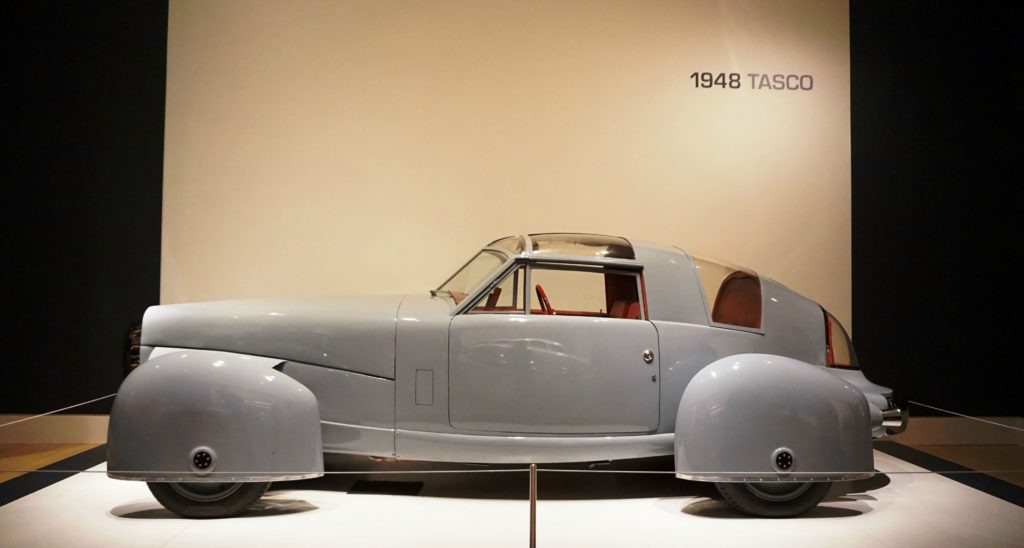

In 1948, Buehrig and investors embarked on an ambitious project with the aspirations of creating a real American rival to European sports cars. Called The American Sportscar Company (TASCO) Prototype, a single vehicle was produced off of a Mercury chassis. Moreover, their engineering emphasized an enclosed cockpit (with aeronautical instruments and controls), a modified V8 engine, and the first-ever T-top roof. In spite of those alluring aspects, the TASCO brand and prototype itself were christened as an unadulterated failure by the public; principally due to its irregular exterior configuration. Three years after the collapse of TASCO, Buehrig smartly patented the plans for his novel glass-roof panels.

Although T-tops were invented, they were still two decades away from widespread use. In Europe, however, a similar design not-yet-known as the ‘Targa’ top was beginning to take off. Introduced to the world at Turin’s motor show in 1957, Fiat’s 1200 succeeded their 1100 sports car with a new engine, body styling, and – most importantly – a redesigned roof structure. Italian coachbuilder Vignale recognized the beauty in this slim sports car’s large greenhouse cabin and set Giovanni Michelotti to work on making it a bit more bespoke. The resultant design was deemed the Fiat 1200 ‘Wonderful’ by Vignale and featured the first removable roof panel system. Although the Wonderful was limited in production, Michelotti’s efforts on the project would serve him while contracted by Triumph in 1961.

Ordered by Triumph, Michelotti used his knowledge from the Wonderful on their TR4. The ‘Surrey Top’ was constructed by utilizing the regular convertible TR4 body and installing a fixed-glass clamshell within a metal frame on the decklid. Between the windshield and this clamshell was a detachable two-piece fabric roof. Its benefits over the convertible variants were found in decreased wind noise and increased inclement weather protection. Like the Fiat, though, very few TR4 were made with the ‘Surrey Top.’ In summation, while the 1950s originated the ‘Targa’ top trend, it was slow to catch on until the 1960s.

By the sixties, automobiles had been around for nearly seventy years. It is within this decade that imposed government statutes – not design teams – began to decide the future shapes and styles of automobiles. One such mandate, proposed with the intent to enhance roll-over safety, was feared by automakers with convertible models and projects. Due to its potential to render convertible designs illegal and uncertainty about securing federal approval if put in place, many car makers opted for a safer alternative form. To test the limitations of ‘Targa’ tops, in 1964, Saab debuted a Catherina prototype with a removable roof. However, it differed from the Fiat and Triumph designs by integrating a protective roll-bar into the rear window; effectively circumventing any legal-blocks by its natural roll protection. Toyota also employed a similar construction on its Sports 800 model a year later. Nonetheless, one company alone is genuinely eponymous with the ‘Targa’ top.

Amidst the success of their 356 Cabriolet models in the United States, Porsche was eager to continue making convertible sports cars. However, with considerable funding wrapped up in the still fresh 911 project, a convertible variation would not only be costly to engineer but possibly unprofitable if the U.S. declared an embargo on them. Realizing the risk was far too considerable, Porsche picked a different direction, and the Targa was conceived. Launched in 1966, the Targa, selected after Porsche’s success in the famous Targa Florio race, became the sole way to get an open-air 911. Porsche’s Targa was unique; an aluminum roll bar provided safety, a vinyl roof panel tightly sealed with the windows to keep the weather out, and the rear window (formed of vinyl and plastic) could be disconnected for a nearly identical convertible experience. Two years later and the design further evolved by introducing a solid-glass clamshell rear window. It was during this year, 1968, that another manufacturer, Chevrolet, brought their convertible counter-attack to market.

Chevrolet was already offering their Corvette in both coupe and convertible versions. Yet in 1968, they elected to proactively produce a T-top version; earning it the title of the first production use of a T-top after the original TASCO concept in 1948. In fact, the appeal of the optional roof panels proved so popular that by 1975, Chevrolet discontinued the sale of convertible Corvettes for nine years. The resurgence of the T-top and the fresh take on the Targa proved to be wildly extolled throughout all of the seventies and early eighties. By skirting regulations, companies such as Ferrari, Lamborghini, BMW, Datsun, Ford, Chrysler, Pontiac, and more guaranteed customers could pop-the-top if they pleased.

Popularity continued to surge through the late eighties, although interest in removable tops was beginning to wane. Porsche completely revised their 911 for 1990 but retained the Targa selection despite a Cabriolet version finally being offered some seven years earlier. Today, Chevrolet and Pontiac’s Camaros/Firebirds still stir up nostalgic memories for countless owners of their fast, rebellious youth on the boulevard with discarded T-tops and Whitesnake blaring. Yet, the storage issues, heft, and inevitable fitment/sealing issues of these panels had become increasingly evident now that semi-convertibles were delving into their third decade of use.

Then, in the mid-nineties, Porsche’s newest 911 generation (the 993), further altered the semi-convertible alternative. The 993 Targa, by use of a sliding section of glass, efficiently alleviated the necessity for cumbersome removal and storage and issues with water sealing. This innovative solution modernized the aging design and allowed it to persist well into the 2010s. It also allowed Porsche to retain the Targa namesake by further distinguishing it from the Cabriolet.

Unfortunately, T-tops did not fare so well with the millennium changeover. Discontinued in 1999, Toyota’s MR2 (SW20) replacement could no longer be had with a T-top option. Then, a year later, Nissan’s 300ZX dropped out. Production of the fourth generation Camaro and Firebird ended in 2002, historically branding them as the last cars produced with T-tops; the Corvette, having switched long ago to a Targa panel.

The reappearance of convertibles during the nineties continually gained momentum through the twenty-first century. Consequently, the removable Targa roof, like its T-top ilk, saw an ever-decreasing application on new autos. While the Corvette continued to option it, Porsche released just the exclusive Carrera GT hypercar with a carbon fiber Targa top during that first decade. With sincere regards, it soon came to be that the vehicles available with Targa roofs solely lingered amongst supercars or small-production sports cars. Acura’s NSX, Lotus’ Elise, Toyota’s Supra, Maserati’s MC12, and Ferrari’s 575 Maranello Superamerica (made with an abnormally different Targa option) are a small sampling of the diminutive possibilities.

Throughout much of the 2010s and on to today, the selection has increasingly dwindled. Within recent times, Targas stayed isolated to Corvettes or ultra-hypercars such as the Bugatti Veyron, Koenigsegg CCX and Agera, and Porsche 918. That example unmistakably highlights a vast disparity in price, availability, and practicality; easily discerned, the Targa has virtually been eradicated from existence.

Nevertheless, in 2014 Porsche again unveiled a revolutionary design reviving the idea of what a Targa could be with their 991 generation of 911. Comprised of a Targa roof that electrically folds back into a self-lifting glass clamshell, the 991 gives customers modern functionality with the prized original 911 Targa appearance. Even Mazda, with their latest MX-5 RF, has taken a crack at an electrically-folding Targa roof and their efforts have been well-received.

In many facets, the Targa and T-top roof were merely disposable designs in automotive manufacturing; perhaps better described as necessary stop-gaps in the continuous attempt to make convertibles viable. Nevertheless, many who have driven them will agree that there is a characteristic charm to semi-convertibles. Not only in their peculiar exteriors but also in their duality. Targa and T-tops indeed find themselves in a distinct spot within the chronology of automotive history and undoubtedly we car enthusiasts are all better off having them around.

Christopher Fussner is the Editor-in-Chief here at WOB Cars and MotoringHistory.com. He writes at his home in Los Angeles, manages a car collection, has a genuine passion for cars and racing, a love of Star Wars, and his favorite dinosaur is Carnotaurus. Did we just become best friends?