Among the legendary names that regularly circulate throughout the automotive industry, few, if any, command more reverence, adulation, and intimidation than the celebrity that is Enzo Ferrari. He is the eponymous founder of the automobile manufacturer and racing teams whose products and brand valuation consistently rank high among the most powerful trademarks worldwide. He curated the development of many a child’s (and adult’s) automotive dreams, but only as means to his ends. The man undoubtedly deserves celebratory accolades among car enthusiasts for his pursuit of performance, for the visions he brought to life, and for the enduring rivalries that resulted all from the cars carrying the name Ferrari.

Amidst a tempestuous snowstorm in February of 1898, Adalgisa Bisbini, wife of Alfredo Ferrari, gave birth to her second child who was proudly named Enzo Anselmo Ferrari. His early life was relatively typical until the age of ten when he witnessed his first motorsport race – a pivotal event that became foundational in his racing aspirations. However, with little formal education and funding, he found it necessary to enlist his skills into the Italian military along with his brother and father during the first World War. 1916 proved to be a misfortunate year for Ferrari when a flu pandemic struck Italian service-men and ultimately caused the deaths of his father and brother who were ground crewmembers in the Italian Air Force. Although Ferrari survived two years later another outbreak of influenza infirmed him and the military was forced to honorably discharged him from service.

After the military Ferrari found himself struggling to make ends meet after his father’s carpentry business failed, with a tenacious spirit, Ferrari fervently outreached to Italian automobile manufactures for jobs. Despite the initial rejection, his perseverance finally paid dividends 1919 when Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali (C.M.N.) hired him to test drive their new cars. It took little time for C.M.N. to recognize his innate potential as a driver and in the same year, Ferrari was promoted to a racing position. During his first outing, Ferrari arrived across the finishing line fourth in his 3.0-liter class at the Parma-Poggio di Berceto Hillclimb. A year later, at the turn of the decade, having established himself as a capable wheelman, Ferrari transferred his talent to Alfa Romeo.

It took little time for Ferrari to establish himself in the upper echelons of the driving rosters. After expertly winning the Coppa Acerbo in 1924, Alfa extended Ferrari’s sponsorship into higher tiers of racing. It took place during this era that he was approached by the parents of departed Italian fighter ace Francesco Baracca about using their son’s Cavallino Rampante (Prancing Horse) coat of arms as his symbol. Since both his father and brother served in the same squadron as the ace pilot, Ferrari graciously accepted their offer. Paying tribute to his family, he chose to adorn the crest with a yellow background to honor his family’s birthplace, Modena. Meant to inspire and intimidate the Prancing Horse emblem proved to be a powerful icon of Ferrari – even early on. However, in 1925, after the passing of legendary racing driver Antonio Ascari, Ferrari reigned himself in from racing, effectively losing the competitive edge.

Even with a diminished drive to push himself to the ragged edge, he kept racing. Nevertheless, his determination still delivered success, and in 1929, under Alfa Romeo’s blessing, he founded their first racing program, Scuderia Ferrari. Given his propensity for leadership, Ferrari was appointed as the first team manager in addition to his racing spot. The same year, he married his long-time wife, Laura Dominica Garello. Two years later she birthed a progeny to the Ferrari legacy, Alfredo (Dino). After the birth, Ferrari retracted himself entirely from racing. At this point, the team’s future began to look promising as Ferrari recruited a crack team of drivers to pilot such well-engineered cars as Alfa Romeo’s Grand Prix masterpiece, the P3.

Unfortunately, Grand Prix racing for Ferrari’s team was dotted with few victories during the 1930s. Despite a well-constructed car and excellent drivers, they were fighting against a technological and mechanical onslaught from the superior German teams of Mercedes and Auto Union. By the conclusion of most races, Alfa Romeo’s race cars were almost always outmatched. A rare moment of elation struck in 1935 when Alfa Romeo and Ferrari dealt their opponents a scathing defeat at the German Grand Prix by securing a first-place podium finish. Yet, after years of travail, Scuderia Ferrari was terminated by Alfa Romeo to form their own Alfa Corse in 1937. Although retained as an advisor, a disagreement in 1939 prompted Ferrari’s immediate retirement from the program.

Barred from forming another racing program or building automobiles, Ferrari elected to become an exclusive parts distributor to prominent racing teams. Although strictly forbidden from creating cars, Auto-Avio Costruzioni (AAC) ignored that restraint by manufacturing and fielding two entries during the 1940 Mille Miglia – although to no success. It was during this same period that World War Two was rapidly engulfing the world and soon Ferrari’s manufacturing abilities were forcibly enlisted to produce munitions and equipment. While this regrettably put a hold on any immediate automobile work, it more importantly allowed the stature of limitation for building cars to expire.

As the war ended, Ferrari found himself free of legal constraints and hastily arranged for the construction of a modern manufacturing facility in Maranello, Italy. With mighty aplomb, nascent Ferrari S.p.A. was founded there in 1947. Three months later and employees saw Enzo Ferrari personally conduct their inaugural test drive of the first genuine Ferrari, the 125S. Two months later, in May, driver Franco Cortese drove his 125S to victory in a race near Rome, cementing their convictions to racing above all else. From there, the wheels, quite literally, just began turning faster as Ferrari dialed up their competitive pursuit of Alfa Romeo and anyone else in the lead.

In 1948, Ferrari entered their first open-wheel competition, securing their first victory later that year. The following year, Ferrari brought home their first major trophy from the 24 Hours of Le Mans having been hard-earned by a Ferrari 166M. It was only a year later when the real romance of the brand started with their enrollment into the newest racing series – Formula 1. It would take a full year for Scuderia Ferrari to find its footing, but once they did they instantly grabbed their first victory at the Silverstone Grand Prix with Jose Frolian Gonzalez at the wheel of a Ferrari 375. It was such an emotionally moving feat for Ferrari to defeat Alfa Romeo that nearby constituents report seeing Enzo joyfully weep. During the two successive Formula 1 seasons, Ferrari would find himself returning home to Maranello with the championship trophy.

As Ferrari began to see successes, he continued to expand his team’s participation in various series during the 1950s and 1960s. However, this came at greater financial responsibility and, much to his chagrin, it was during this era he started to sell production cars to clients. Although he was a capable, cunning salesman, it was his racing success, and the exotic allure of the Pininfarina designed performance cars that made them quick and easy sellers to high-profile customers throughout Europe. Then, in 1954, the opening of his first showroom in Manhattan, New York, allowed Hollywood’s elite to buy into the cache of Ferrari’s prestigious pedigree.

Despite seemingly ever-growing racing and financial success, the 1950s were also a personally tumultuous time for Ferrari. In 1956, his only son Dino, who was born with muscular dystrophy passed away. The loss was devastating to Ferrari and ultimately catalyzed his reclusive behavior in the later years of his life. Racing inherently is a risky, life-threating business but this was multiplied while working under il Commendatore (Ferrari), who was well-known to mentally pit drivers against each other and use favoritism to keep them on a competitive knifes-edge. This competitive standard was even employed on factory workers and engineers, who were often staged against each other for Ferrari’s favor. Ferrari himself is famously quoted by saying “[It] is a great mania to which one must sacrifice everything, without reticence, without hesitation,” with regards to professional racing drivers, but true to form he practiced it in all of life’s aspects. With that mentality, it comes as a little surprise that many illustrious names perished behind the wheel of a Ferrari during this period, such as Wolfgang von Trips, Peter Collins, Luigi Musso, and four others between 1955 and 1965.

The most unfortunate of these was the tragic death of Marquis Alfonso de Portago during the Mille Miglia in 1957. The Mille Miglia had been raced on public streets around the Italian countryside since 1927. Nonetheless, the competition continued even as decades passed with engineering and technology serving only to make the race cars faster across the poorly paved country roads. This complacency was augmented with spectators who regularly watched along the sides of the streets without protective barricades to separate them from the speeding cars regularly traveling more than one-hundred miles an hour. It was at speeds over 155mph, that Portago suffered a tire blowout in his Ferrari 335S sending the vehicle into a crowd of spectators killing himself, his co-pilot, and nine onlookers.

The tragedy struck Ferrari and the tire manufacturer hard when they were charged with involuntary manslaughter. Although they were eventually acquitted the negative publicity lingered for many years. It was particularly grim for Ferrari who was viewed as a national icon only preceded in importance by the Pope. So infuriated were the citizens of Italy, that the L’Osservatore Romana newspaper did not hesitate to print a condemning piece comparing Ferrari’s management of his racers to the god Saturn, who legendarily devoured his sons to prolong himself. However focused on winning he was, Ferrari was not heartless, and the losses weighed heavily upon him. Instead, he elected to establish limits on how personal his relationships with drivers could be so as not to hurt himself further.

As mentioned, the 1960s were a troublesome time in Maranello. Early on in the decade (1961) nearly all of the top brass at Ferrari up and left to form their own company due to issues with his wife’s involvement in the company, his management style, and abrasive personality. The walkout cut deep, and production and development stumbled in the wake. However, with these vacancies, Ferrari wasted no time in filling them by immediately appointing their underlings as successors to the available positions to make up time. The walkouts may have caused significant disruption for a time, but undeterred, progress went on with Ferrari’s new production and racing model the 250 and Formula 1 campaigns. Recoiling from the grand departure and difficulty throughout the 1950s, Ferrari still went on to win nine victories at Le Mans and two F1 Manufacturer Championships that were grabbed all before 1966.

On the race track, Ferrari was dominating, but financially (even with road-car production sales), they were overstretched. In 1963, Ferrari met with Ford regarding talks of a stake buyout. When the brokerage fell through over Ferrari wanting to retain management of racing teams, bad blood was spilled. It was soon after that a new rivalry began when Ford took the fight to Ferrari on the race track to spite them over the soured deal. Regardless of the Ford vs. Ferrari battle, by the end of the decade a partnership with FIAT was settled for a 50% stake in Ferrari while Enzo retained 100% control of racing teams – effectively saving the insolvent company.

Knowing that his age was building, and having saved his company, Ferrari began implementing replacements for his roles. Two years after the FIAT settlement, in 1971, Ferrari relinquished command of the road car division and three years after that he self-appointed Luca Cordero di Montezemolo to the head of Sporting Director/Formula 1 team management. The torch had been passed.

In 1977, Ferrari officially resigned from the presidency at Ferrari S.p.A, although he still maintained control – legally. A year later, his wife, passed away and he finally admitted to fathering a second son (Piero) to his mistress, Lina Lardi in 1945. With his age now numbering into the 80s, Ferrari grew even more solitary. He was seldom seen outside Maranello or Modena, except at Grand Prix events around Italy and it is known on only one occasion, in 1982, of him leaving the country to attend a meeting in Paris. In the end, his death came while in Maranello on August 14th, of 1988 at the age of 90.

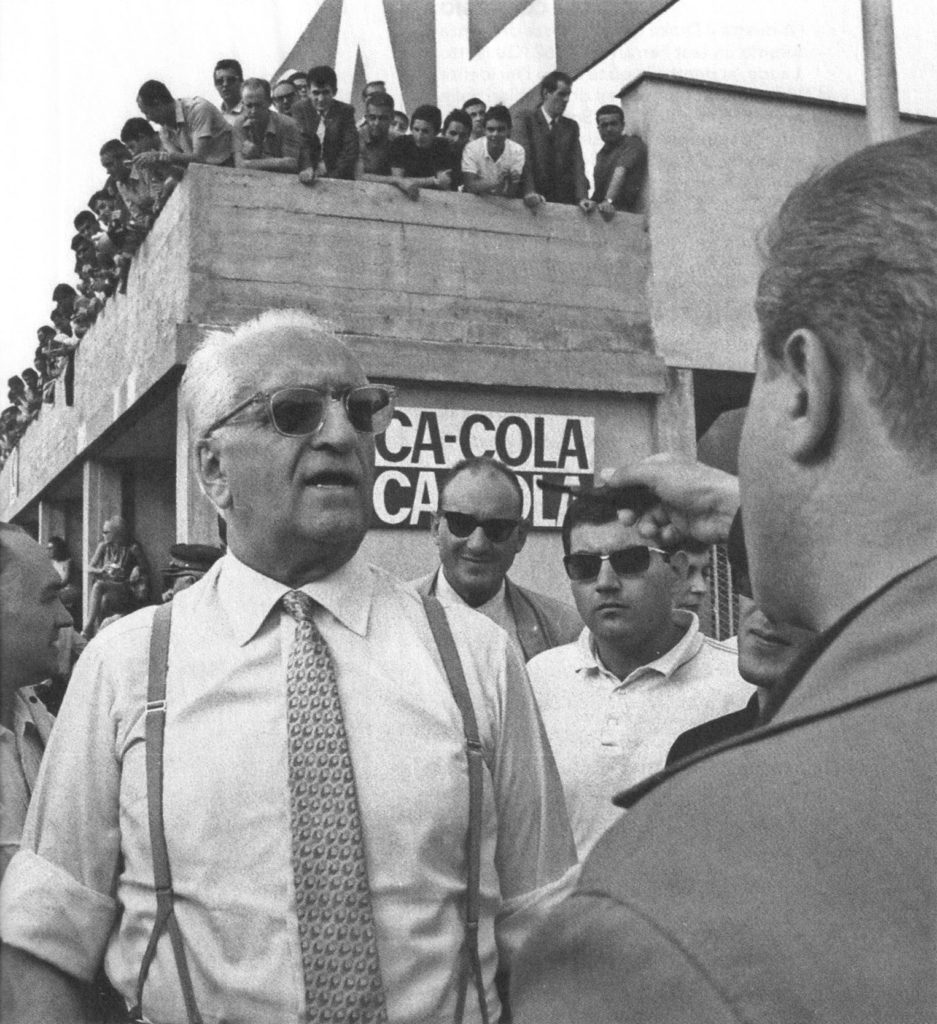

The legacy he cultivated, simply put, is monumental, enticing, and energetic. While it is true that his resolute approach toward racing perfection was controversial, it put his company on the map, accruing over 4,000 racing victories and 13 Formula 1 World Championships during his time. His accomplishments and larger-than-life personality, along with his iconic dark sunglasses, have well-earned his celebrity status. Ultimately, it is his defiant attitude of victory at all costs that is imbued into every car which bear his name that makes them so alluring to us.

Christopher Fussner is the Editor-in-Chief here at WOB Cars and MotoringHistory.com. He writes at his home in Los Angeles, manages a car collection, has a genuine passion for cars and racing, a love of Star Wars, and his favorite dinosaur is Carnotaurus. Did we just become best friends?